Original article posted by NASA on November 17, 2022.

Webb spies early galaxies

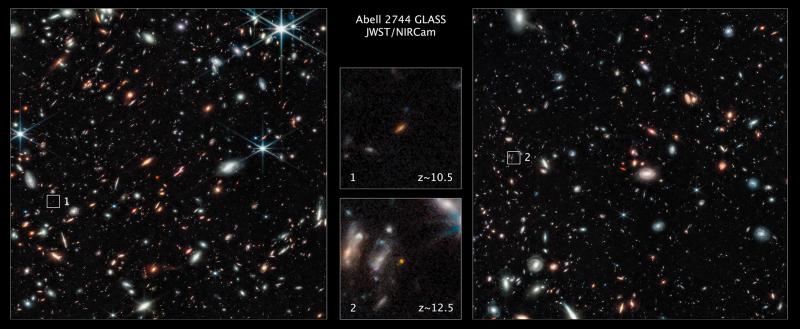

A few days after officially starting science operations, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope propelled astronomers into a realm of early galaxies, previously hidden beyond the grasp of all other telescopes until now. Tommaso Treu of the University of California at Los Angeles, principal investigator on one of the Webb programs, said:

Everything we see is new. Webb is showing us that there’s a very rich universe beyond what we imagined. Once again the universe has surprised us. These early galaxies are very unusual in many ways.

The Astrophysical Journal Letters has published two peer-reviewed research papers on the subject. Marco Castellano of the National Institute for Astrophysics in Rome, Italy, led the first study, published October 18, 2022. Rohan Naidu of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts, led the second study, published November 17, 2022. These initial findings are from a broader Webb research initiative involving two Early Release Science (ERS) programs: the Grism Lens-Amplified Survey from Space (GLASS), and the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science Survey (CEERS).

Early galaxies surprise astronomers

With just four days of analysis, researchers found two exceptionally bright galaxies in the GLASS-JWST images. These galaxies existed approximately 450 and 350 million years after the Big Bang (with a redshift of approximately 10.5 and 12.5, respectively). However, future spectroscopic measurements with Webb will help confirm.

Astronomers believe the more distant GLASS galaxy, GLASS-z12, dates back to 350 million years after the Big Bang. About GLASS-z12, Naidu said:

With Webb, we were amazed to find the most distant starlight that anyone had ever seen, just days after Webb released its first data.

The previous record holder is galaxy GN-z11, which existed 400 million years after the Big Bang (redshift 11.1). Hubble and Keck Observatory deep-sky programs identified it in 2016.

Castellano said:

Based on all the predictions, we thought we had to search a much bigger volume of space to find such galaxies.

Paola Santini, fourth author of the Castellano et al. GLASS-JWST paper, said:

These observations just make your head explode. This is a whole new chapter in astronomy. It’s like an archaeological dig, and suddenly you find a lost city or something you didn’t know about. It’s just staggering.

Pascal Oesch at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, second author of the Naidu et al. paper, said:

While the distances of these early sources still need to be confirmed with spectroscopy, their extreme brightnesses are a real puzzle, challenging our understanding of galaxy formation.

Unexpected brightness

The Webb observations nudge astronomers toward a consensus that an unusual number of galaxies in the early universe were much brighter than expected. This will make it easier for Webb to find even more early galaxies in subsequent deep sky surveys, say researchers.

Garth Illingworth of the University of California at Santa Cruz, a member of the Naidu/Oesch team, said:

We’ve nailed something that is incredibly fascinating. These galaxies would have had to have started coming together maybe just 100 million years after the Big Bang. Nobody expected that the dark ages would have ended so early. The primal universe would have been just one hundredth its current age. It’s a sliver of time in the 13.8-billion-year-old evolving cosmos.

Erica Nelson of the University of Colorado, a member of the Naidu/Oesch team, noted that:

… our team was struck by being able to measure the shapes of these first galaxies; their calm, orderly disks question our understanding of how the first galaxies formed in the crowded, chaotic early universe.

This discovery of compact disks at such early times was possible because of Webb’s sharper images, in infrared light, compared to Hubble. Treu said:

These galaxies are very different than the Milky Way or other big galaxies we see around us today.

Why so bright?

Illingworth emphasized that the two bright galaxies found by these teams have a lot of light. He said one option is that they could have been very massive, with lots of low-mass stars, like later galaxies. Alternatively, they could be much less massive, consisting of far fewer extraordinarily bright stars, known as Population III stars. Long theorized, they would be the first stars ever born, blazing at blistering temperatures and made up only of primordial hydrogen and helium. They formed before stars could later cook up heavier elements in their nuclear fusion furnaces. Astronomers have not seen such extremely hot, primordial stars in the local universe.

Adriano Fontana, second author of the Castellano et al. paper and a member of the GLASS-JWST team, said:

Indeed, the farthest source is very compact, and its colors seem to indicate that its stellar population is particularly devoid of heavy elements and could even contain some Population III stars. Only Webb spectra will tell.

Scientists base current Webb distance estimates to these two galaxies on measuring their infrared colors. Eventually, follow-up spectroscopy measurements showing how the expanding universe has stretched the light will provide independent verification of these cosmic yardstick measurements.

Bottom line: The James Webb Space Telescope has captured two extremely early galaxies that are much brighter than astronomers expected they would be.

Source: Early Results from GLASS-JWST. III. Galaxy Candidates at z ~9–15*

Source: Two Remarkably Luminous Galaxy Candidates at z ≈ 10–12 Revealed by JWST

The post Bright, early galaxies surprise astronomers first appeared on EarthSky.

0 Commentaires