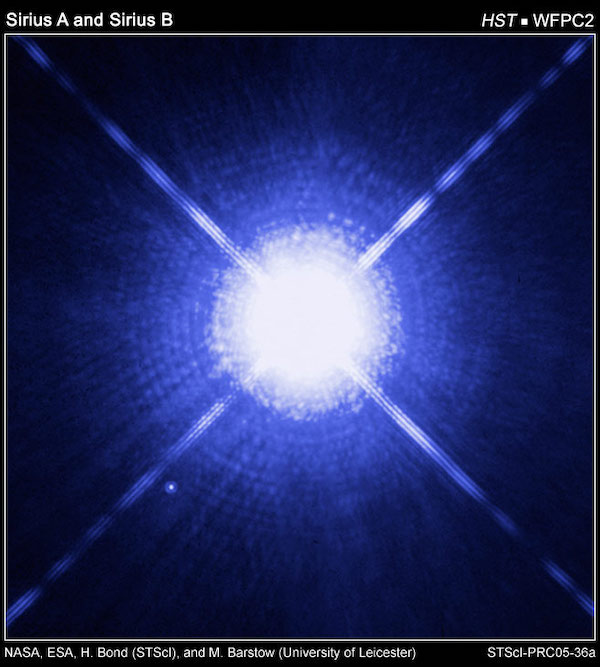

The brightest star in our sky, Sirius, and its white dwarf companion, Sirius B, are currently farthest apart from our perspective. The two stars orbit each other with a period of about 50 years, and they’re having their maximum separation of 11 arcseconds now. While it’s always a challenge to see dim Sirius B next to brilliant Sirius, presently you have a bit of an advantage. Learn how to see Sirius B, below.

The 2024 lunar calendars are here! Best Christmas gifts in the universe! Check ’em out here.

How to see Sirius’ companion

By Florin Andrei. Reprinted with permission.

Sirius the Dog Star is the brightest star in the night sky, visible anywhere on Earth except the far north. If you live in the Northern Hemisphere at a temperate latitude, Sirius is the very bright white star due south every winter in the evening. But did you know that Sirius is also a double star? The companion, Sirius B, also known as the Pup, is a very small star orbiting the primary. You can see it using even small amateur telescopes. It’s not easy to spot but can be done if you follow certain guidelines. Here’s how to do it.

Sirius A and B

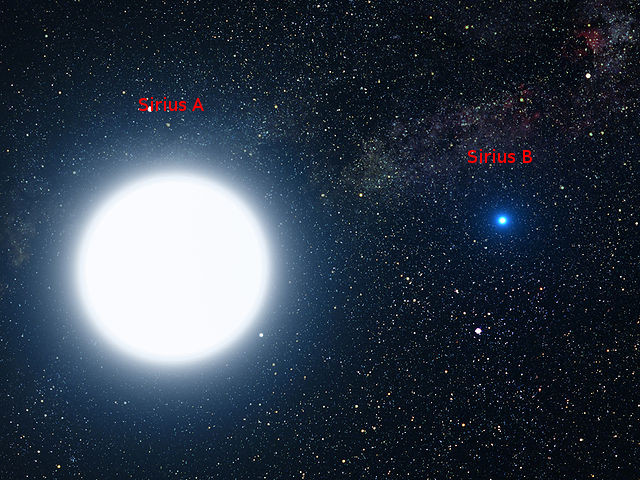

While Sirius A, the main component, is a large white star twice as massive as the sun, Sirius B, the companion, is a white dwarf. Sirius B is about as massive as the sun, but very small at about the same volume as Earth. Around 120 million years ago, Sirius B was a large white star five times as massive as the sun, but it has since passed through the red giant phase. Now, it’s the dead remnant of a formerly active star.

Currently, Sirius B is not generating any new heat, as the fusion reactions in its core have stopped. It is steadily cooling down, a process that will take a very long time, because it’s still pretty hot as of now: 25,200 Kelvin (44,900 degrees F or 24,900 C). Basically, Sirius B is the white-hot dead body of a formerly large and very active star. While B is twice as hot as the primary (Sirius A), its very small size makes it much less bright. Sirius B’s luminosity is about 10,000 times less than that of Sirius A.

Tracking the orbit of Sirius B

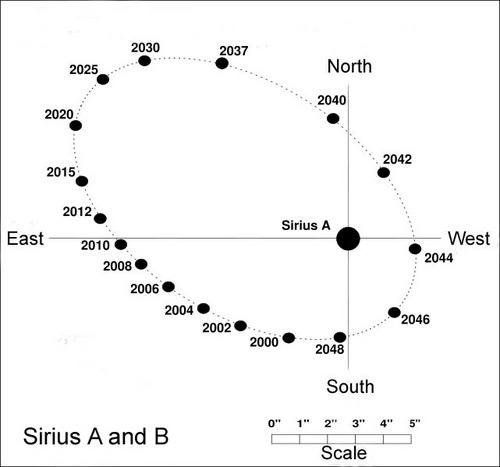

The two stars, the main component and the companion, orbit each other at a distance of approximately 20 astronomical units (AU). That is about the same as the distance between the sun and Uranus. As a result, when we observe them from Earth, Sirius B appears to describe an ellipse around Sirius A with a period of 50 years.

Seen from Earth, the separation between Sirius A and B varies between 3 and 11 arcseconds on a 50 year cycle. And now they’re at 11 arcseconds apart, so it’s a great time to look for Sirius B. But you have to follow certain rules, since this is not an easy target.

Why this is a difficult observation

Sirius is a double star, with pretty good separation, but with a very large difference in brightness between its stars. Based on separation alone (3 to 11 arcseconds), it should be an easy double to split. But the brightness imbalance is staggering. Sirius B is often lost in Sirius A’s tremendous glare, so you have to take special measures to make B visible.

If you’re an experienced astronomer, you can probably skip some of the following recommendations, as they are probably a matter of your daily routine. But if you’re a beginner, keep reading.

In any case, don’t worry. Sirius B is definitely visible even in a small amateur telescope throughout the 2020s and 2030s. A good 100mm (4-inch) scope or larger should split it in the upcoming years. You can do it. Just play by the rules and be persistent. You will likely not succeed on your first or second attempt. But keep trying, and eventually you’ll see it.

Best time to see Sirius B, and corresponding location on the sky

If you live in the Northern Hemisphere, in the temperate zone, the best time to attempt observing Sirius B is in winter, January and February for the most part. This is when Sirius is at its highest in the sky at a convenient early hour. December is also fine if you don’t mind staying up late, or November if you’re basically an owl. In March, you want to be ready as soon as the sky is dark enough. It is important that the star is not too low in the sky, as seeing (turbulence) becomes much worse close to the horizon, and seeing is absolutely crucial for this observation.

At the 1st of February, you should be outside and already observing around 10 p.m. New Year’s Day, the best time (when Sirius is at the highest point) is around midnight. The 1st of March, the best time is 8 p.m. Come April 1st, Sirius already begins to descend after sunset, so the best observational season is coming to an end.

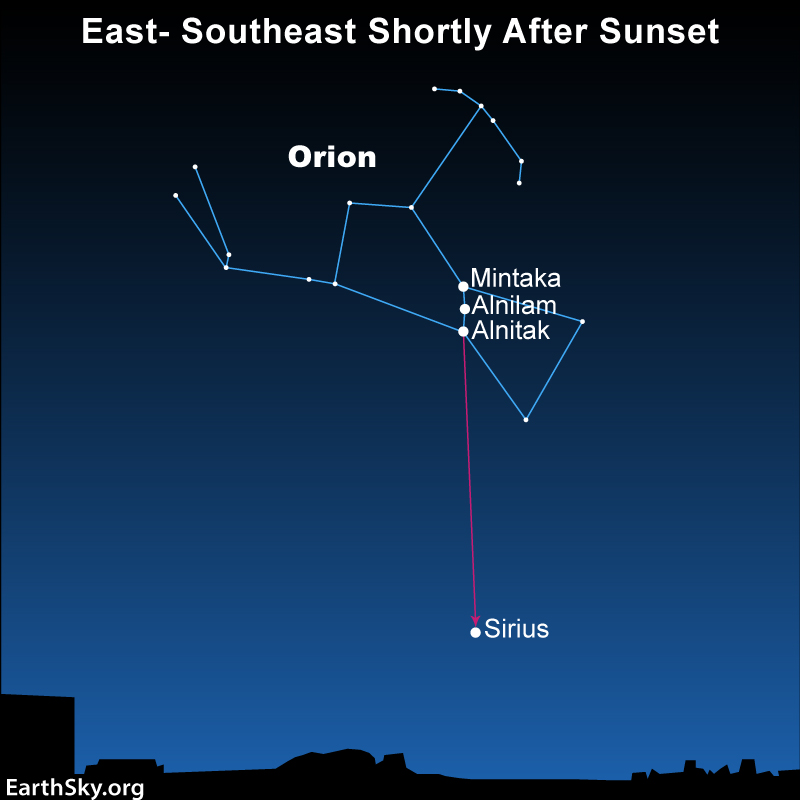

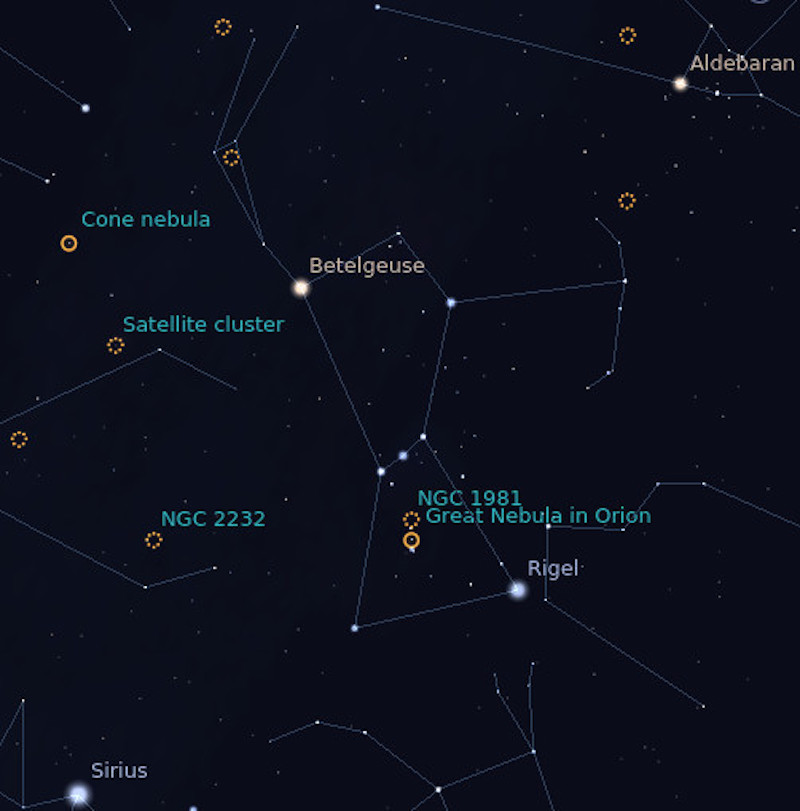

After you know what time to observe, go outside and look south. That very bright white star not too high in the sky is Sirius. To its right (west), you can see the great constellation of Orion, with bright red Betelgeuse near the top, then the Belt of three stars, then white Rigel at the base.

The importance of seeing

What we in astronomy call seeing is what others call turbulence. Seeing (or air turbulence) blurs the image whenever you’re attempting a high-resolution observation from Earth. It depends on the weather, location and a number of other factors. It is predictable to some extent.

First, go to the Clear Sky Chart site to find the outlook near you. Then, choose a location nearest your place. Next, look at the fourth row in the chart, the one called “Seeing.” When the chart is dark blue, that means good seeing. When the chart is white or light blue, the prediction for seeing is bad.

Excellent seeing is crucial to this observation. It is the most important factor. To see Sirius B, nothing short of excellent seeing will work. Yet, even if the seeing forecast is merely “good,” you should still attempt an observation. Here’s why: There can be brief moments when the air becomes very still even during more vigorous turbulence, and that’s enough to get a short glimpse of Sirius B. But if the forecast is bad, there’s probably no point in trying.

Telescope considerations for seeing Sirius B

Is the primary mirror clean enough?

If your telescope is an open reflector (such as a Dobsonian), dust accumulating on the primary mirror will increase light scattering. If you have cleaned the mirror in the last few months, then feel free to ignore this part. But if it’s been a year or more since the last mirror clean-up, it’s time to give it a bath.

Be very gentle. Use your sense of touch to detect when you hit a dust mote lodged on the surface and avoid dragging it across. Or use cotton balls if your fingers are less sensitive and you’re afraid you’ll scratch the mirror. But apply almost no pressure with the cotton.

At the end, rinse it with plenty of distilled water, then leave it alone and don’t touch it with anything afterward.

Since it’s recommended you do this procedure once a year, perhaps it’s a good idea to schedule it in early January, before you start hunting for Sirius B.

Are the eyepieces clean enough?

The eye-facing lens of any eyepiece is contaminated by grease from eyelashes within seconds of starting an observation. This creates a haze that reduces contrast. It is recommended to clean the lens before any difficult observation. This is the best method.

Use high-concentration alcohol (90% or better) and Q-tips. Make sure the Q-tips are not soaked; if the Q-tip is just a bit wet, that’s when cleaning is most successful. If the Q-tip makes a puddle of alcohol on the lens that persists for a long time, you’re using too much liquid.

Is the telescope collimated?

Collimation is crucial for any high-resolution observation. If previously you’ve only done superficial collimation, now it’s time to get down to business and do it right. There are many techniques and tools for collimation. Here’s a good primer for Newtonian reflectors (such as Dobsonians) using simple tools:

Collimation is a vast topic: you could literally write a whole book discussing nothing but collimation, so keep learning and apply what you learn.

When seeing is good, you could plug a high-power eyepiece into your scope and do a star test to verify collimation. The star test is the ultimate authority for telescope performance, so at least learn the basics.

Is the telescope cooled down?

To deliver peak performance, a telescope must be at thermal equilibrium with the environment. Read about thermal issues at here and here.

Even if you don’t have a mirror fan, at least take the scope outside one hour before you start the observation, and let it cool down to ambient temperature. This should be enough to reap most benefits of thermal equilibrium.

Okay, now go ahead and look for Sirius B

Seeing is great, Sirius is high in the sky, the telescope is in perfect shape … now it’s time to look at Sirius, right?

Not so fast. Before that, take a look to the west (to the right) of Sirius, and observe the large constellation of Orion.

On the above map, Betelgeuse is on top, bright and red. In the middle, there’s the “Belt” made of 3 stars. Then at the bottom there’s Rigel, a bright white star.

Rigel itself is a double star. The separation between Rigel A and B is similar to the separation between Sirius A and B. Except the brightness difference between Rigel A and B is much less than the difference between Sirius A and B, which makes Rigel a much easier double to split.

So grab a high-power eyepiece, plug it into the scope, and point the instrument at Rigel. You’ll see a bright white star, and nearby a much smaller star, which is supposed to be white but looks quite yellow to me. Try to memorize the distance between Rigel A and B, because it’s similar to the current distance between Sirius A and B.

If you can’t see Rigel B, either seeing is so bad or your scope is out of whack, and there’s no point to even try to see Sirius B.

Time to actually describe the observation of Sirius B

You should use very high magnification. Forget what you’ve heard on forums or from word-of-mouth about “magnification limits;” just plug in a strong eyepiece. For a 150mm (6-inch) scope, 300x is not too much; for a 200mm (8-inch) scope, up to 400x; for a 300mm (12-inch) scope, up to 600x. Try the highest magnification available, then back off a little if things are too fuzzy. You should not use less than half the magnifications indicated above: In other words, for a 200mm (8-inch) scope, stay between 200x and 400x.

Point the scope at Sirius, turn off tracking (if your scope has it), and let the star drift across the field. Sirius B is currently close to due east from A (east-northeast), so it should be trailing the primary star, following the primary a little bit off to the side of A’s trajectory.

A comfortable chair helps you relax and breathe slowly. Keep looking at the primary star and be mindful of the surrounding area trailing the star as it drifts across the field. There will be a lot of light scattered from the primary, making it hard to see anything in the vicinity. Just relax and keep watching.

Sometimes the eye is covered in excess fluid (tears, basically) which blurs the image. Back off from the eyepiece a few millimeters and blink slowly and firmly a couple times (but don’t squeeze it shut too hard), then resume.

How Sirius B appears

In theory, Sirius B should be just outside the bundle of shimmering brightness centered on Sirius A, but – being pretty weak – it’s hidden by the tremendous glare from the primary. Once in a while, something will coalesce out of nothing, and you’ll see the unmistakable round pattern of a star.

Even in good seeing, it’ll wink in and out of existence. Or you’ll see it for a few moments, then it’ll vanish again for a long time. Don’t confuse it with a diffraction artifact from the primary. Stars are round, whereas artifacts are typically more linear or oddly shaped.

Only when seeing is very good will you be able to see Sirius B for extended periods of time. Usually it’s more elusive than that.

When your eyes are tired, take a break, go observe the Great Orion Nebula or Rigel A/B again. Then get back to hunting Sirius B.

If you fail at your first attempt, well, that’s normal. Try again tomorrow. It’s hard to catch the perfect seeing required, so persistence is important. Perfect seeing, a telescope in perfect shape, high magnification, and persistence: That’s how it’s done.

Good luck, and clear skies.

Bottom line: Now is a great time to see Sirius’ dim companion, the white dwarf Sirius B. The two are currently at their maximum separation of 11 arcseconds, as viewed from Earth.

The post Sirius B: Now is the best time to see Sirius’ companion first appeared on EarthSky.

0 Commentaires