By Linus Milinski, University of Oxford; Fernando Nodal, University of Oxford; Victoria Bajo Lorenzana, University of Oxford and Vladyslav Vyazovskiy, University of Oxford

Tinnitus can have serious impacts on your health

Around 15% of the world’s population suffers from tinnitus, a condition causing someone to hear a ringing or buzzing without any external source. It is often associated with hearing loss.

Not only is tinnitus annoying for sufferers, it also has a serious effect on mental health, often causing stress or depression. This is especially the case for patients suffering from tinnitus for months or even years.

There is currently no cure for tinnitus. So finding a way to better manage or treat it may help many millions of people worldwide.

One area of research that can help us better understand tinnitus is sleep. There are many reasons for this. First, tinnitus is what’s called a phantom percept. It happens when our brain activity makes us see, hear or smell things that aren’t there. Most people only experience phantom perceptions when they are asleep. But for people with tinnitus, they hear phantom sounds while they are awake.

The second reason is because tinnitus alters brain activity. So certain areas of the brain – such as those involved in hearing – are potentially more active than they should be. This also explains how phantom percepts happen. When we sleep, activity in these same brain areas also change.

A recent study identified a couple of brain mechanisms that underlie both tinnitus and sleep. Better understanding of these mechanisms – and the way the two are connected – may help us find ways to manage and treat tinnitus.

The John Hopkins Medicine tinnitus page

The American Tinnitus Association

How sleep is related

When we fall asleep, our body experiences multiple stages of sleep. One of the most important stages of sleep is slow-wave sleep or deep sleep. Researchers believe this is the most restful stage of sleep.

During slow-wave sleep, brain activity moves in distinctive waves through different areas of the brain. Thus activating large areas together – such as those involved with memory and processing sounds – before moving on to others. Slow-wave sleep appears to allow the brain’s neurons – specialized brain cells which send and receive information – to recover from daily wear and tear. Slow-wave sleep also helps us feel rested and appears to be important for our memory.

Not every area of the brain experiences the same amount of slow-wave activity. It is most pronounced in areas we use while awake, such as those important for motor function and sight.

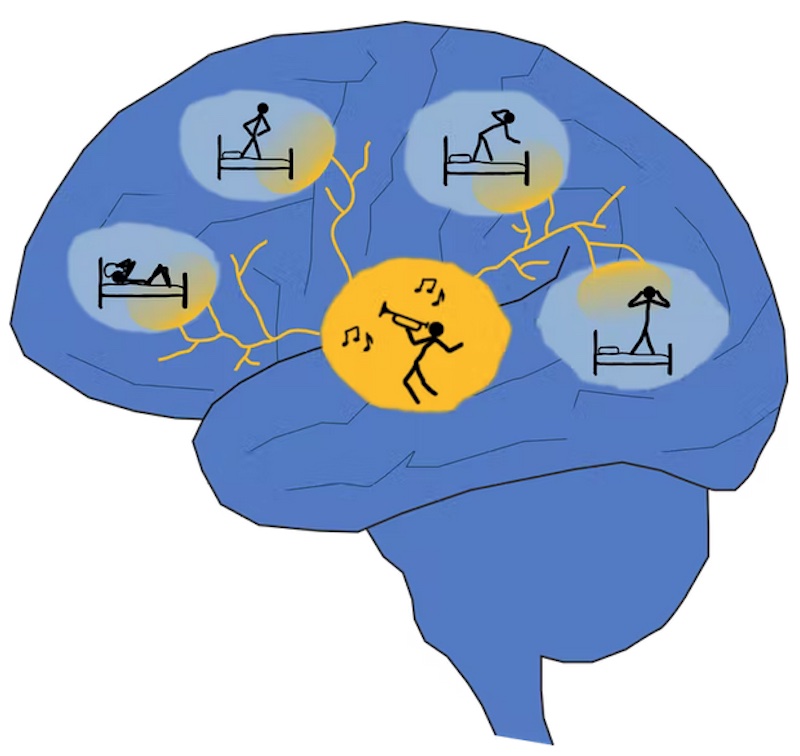

But sometimes, certain brain areas are overactive during slow-wave sleep. This happens with sleep disorders such as sleep walking.

A similar thing happens in people with tinnitus. Researchers think that hyperactive brain regions stay awake in the otherwise sleeping brain. This explains why many people with tinnitus experience disturbed sleep and night terrors more often than people who don’t have tinnitus.

Tinnitus may result in more light sleep

Tinnitus patients also spend more time in light sleep. Researchers believe that tinnitus keeps the brain from producing the slow-wave activity needed to have a deep sleep, resulting in light and interrupted sleep.

But even though tinnitus patients get less deep sleep on average than people without tinnitus, research suggests that some deep sleep is hardly affected by tinnitus. This may be because the brain activity that happens during the deepest sleep actually suppresses tinnitus.

There are a couple of ways the brain may suppress tinnitus during deep sleep. The first has to do with the brain’s neurons. After a long period of wakefulness, neurons in the brain are thought to switch into slow-wave activity mode to recover. The more neurons in this mode together, the stronger the drive is for the rest of the brain to join.

We know that the drive for sleep gets strong enough that neurons in the brain will eventually go into slow-wave activity mode. And since this especially applies to brain regions overactive during wakefulness, we think that tinnitus might be suppressed as a result of that.

Deep sleep may suppress tinnitus

Slow-wave activity also interferes with the communication between brain areas. During deepest sleep this may keep hyperactive regions from disturbing other brain areas and from interrupting sleep.

This explains why people with tinnitus can still enter deep sleep, and why tinnitus may be suppressed during that time.

Sleep is also important for strengthening our memory, by helping to drive changes in connections between neurons in the brain. We believe that changes in brain connectivity during sleep contribute to what makes tinnitus last for a long time after the initial trigger. Hearing loss is often an initial trigger for tinnitus.

New treatments

We already know that the intensity of tinnitus can change throughout a given day. Investigating how tinnitus changes during sleep could give us a direct handle on what the brain does to cause fluctuations in tinnitus intensity.

We may be able to manipulate sleep to improve the wellbeing of patients and possibly develop new treatments for tinnitus. For example, sleep disruptions can be reduced and slow-wave activity can be boosted through sleep restriction paradigms, where patients are told to only go to bed when they’re actually tired. Boosting the intensity of sleep could help us better see the effect sleep has on tinnitus.

While we suspect that deep sleep is the most likely to affect tinnitus, there are many other stages of sleep that happen. One of these are rapid eye movement – or REM sleep – each with unique patterns of brain activity.

In future research, both the sleep stage and tinnitus activity in the brain could be tracked at the same time by recording brain activity. This may help to find out more about the link between tinnitus and sleep and help researchers understand how tinnitus may be alleviated by natural brain activity.

![]()

Linus Milinski, Doctoral Researcher in Neuroscience, University of Oxford; Fernando Nodal, Departmental Lecturer, Auditory Neuroscience Group, University of Oxford; Victoria Bajo Lorenzana, Associate Professor of Neuroscience, University of Oxford and Vladyslav Vyazovskiy, Professor of Sleep Physiology, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bottom line: Around 15% of the world’s population suffers from tinnitus, or a ringing in the ears. Scientists believe there is a link between tinnitus and sleep.

Read more: People sleep less before a full moon

The post Tinnitus seems to be linked to sleep first appeared on EarthSky.

0 Commentaires