Magnificent great frigatebirds can routinely fly over a mile high, and sometimes twice that high, or even higher. And that’s why scientists have been employing birds with backpacks for Earth studies. The American Geophysical Union published this original story on December 12, 2023. Edits and video by EarthSky.

Scientists often field check their findings, heading outside to see if computer models match with what is happening in the real world. But doing so is challenging when the field is 2 1/2 miles (4,000 m) up. Enter a new field assistant: the great frigatebird.

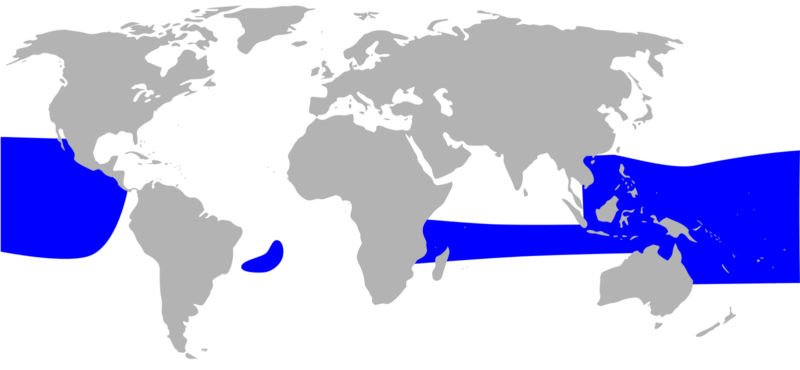

Great frigatebirds live in tropical regions and routinely fly to 1.25 miles (2,000 meters) in altitude. Occasionally they even reach heights of 2.5 miles (4,000 meters). A new study shows that great frigatebirds equipped with tiny sensors can give detailed information about the planetary boundary layer. The planetary boundary layer is the dynamic atmospheric layer closest to Earth. It’s where we experience weather, air quality and climate impacts. Scientists presented the new research at the AGU Annual Meeting on Wednesday, December 13, 2023, in San Francisco and online.

The 2024 lunar calendars are here! Best Christmas gifts in the universe! Check ’em out here.

Investigating the planetary boundary layer

The planetary boundary layer connects the atmosphere with the surface ocean, land and ice. It rises and falls throughout the day. Ian Brosnan, a marine scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center who led the work, said:

Many weather and climate processes are related to that fluctuation. So understanding planetary boundary layer dynamics is fundamental to answering a lot of questions about the Earth system.

Current techniques typically rely on ground-based measurements or remote sensing, but for far-flung regions over the oceans, Brosnan said:

… getting in situ samples of any sort at scale is a challenge.

Enter the great frigatebirds

Brosnan’s co-author, NASA ecologist Morgan Gilmour, previously used sensor-laden great frigatebirds to assess whether the boundaries of a marine protected area around Palmyra Atoll in the Pacific Ocean protected the animals within it. Brosnan suspected the frigatebirds’ flights were related to the planetary boundary layer. If so, Gilmore’s project had also collected critical planetary boundary layer samples. Brosnan said:

I instantly thought the birds could be traveling to the top of the planetary boundary layer, turning around, and coming back down. And they’re probably covering a pretty broad area, too.

To check if the birds’ flight patterns matched planetary boundary layer altitudes, they compared planetary boundary layer measurements from 2006-2019 analysis to frigatebirds’ flights. They found that the long-term average planetary boundary layer heights in that area very closely matched the bird’s altitude data. Brosnan’s hunch was right.

The tagged frigatebirds had sampled temperature profiles in the planetary boundary layer and had no trouble collecting data during cloudy weather or at night, unlike traditional sampling approaches. Brosnan said:

These novel approaches to using animal tracking data can help NASA measure the planetary boundary layer and improve climate predictions and weather and air quality forecasts.

Internet of Animals

Brosnan mentioned that after hearing from interagency scientists about how important global, satellite-based animal tracking data was for their research projects, NASA created the Internet of Animals project. This allows scientists to integrate data from remote sensing measurements with data from sensors on animals, now including the great frigatebird planetary boundary layer data.

Brosnan said their work is a good example of how interagency and interdisciplinary collaborations can help tackle larger science questions:

One of the things we’re trying to do is bridge between these two communities – animal tracking and atmospheric science – and see if we can enrich the work that we both do.

Bottom line: A new study from NASA’s ‘Internet of Animals’ project shows that high-flying great frigatebirds can provide detailed sampling of the atmospheric layer located closest to Earth, where weather and climate directly impact us.

Read more: Animals on the brain? There’s a scientific reason

The post Birds with backpacks to help study Earth’s atmosphere first appeared on EarthSky.

0 Commentaires