This story comes from Northwestern News, with edits by EarthSky.

Ultracool dwarf binary stars

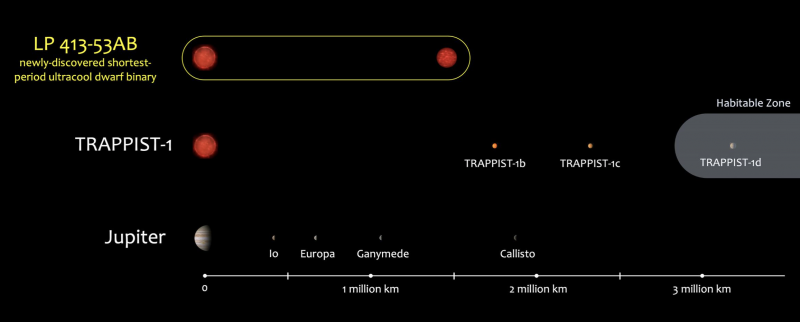

Cool red dwarfs are the most common sort of star in our Milky Way galaxy. But astronomers said yesterday (January 10, 2022) that they’ve discovered what they called the tightest ultracool dwarf binary system ever observed. The two stars in this system both are extremely low in mass. And they’re so cool they emit their light mostly in the infrared – what we’d perceive as heat – and so are completely invisible to the human eye. What’s more, the stars are close together. They take less than an Earth-day to complete a single orbit around one another.

That’s in contrast to Mercury, our sun’s innermost planet, which takes 88 Earth-days to orbit our sun. So a “year” in this close, cool dwarf binary system lasts just 20.5 Earth-hours. And that fact prompted one of the researchers to comment:

It’s amazing to see something happen in the universe on a human time scale.

We knew they should exist

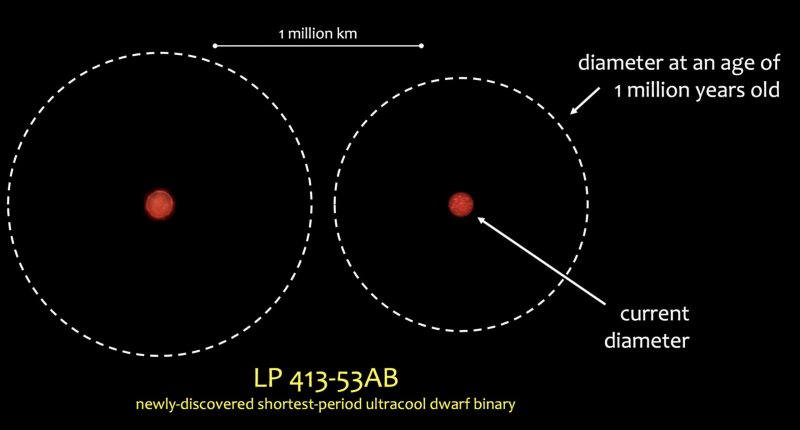

The newly discovered system is named LP 413-53AB. Prior to finding it, astronomers had detected only three short-period ultracool dwarf binary systems, all of which are relatively young, up to 40 million years old. LP 413-53AB is estimated to be billions of years old – similar age to our sun – but has an orbital period that is at least three times shorter than the all ultracool dwarf binaries discovered so far.

Chih-Chun “Dino” Hsu of Northwestern University, the astrophysicist who led the study, commented:

In principle, we knew these systems should exist. But no such systems had been identified yet.

Hsu presented this research during a press briefing at the 241st Meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle on January 10. He began this study while a Ph.D. student at UC San Diego, where he was advised by Adam Burgasser.

The team first discovered the strange binary system while exploring archival data. Hsu developed an algorithm that can model a star based on its spectral data. By analyzing the spectrum of light emitted from a star, astrophysicists can determine the star’s chemical composition, temperature, gravity and rotation. This analysis also shows the star’s motion as it moves toward and away from the observer, known as radial velocity.

When examining the spectral data of LP 413-53AB, Hsu noticed something strange. Early observations caught the system when the stars were roughly aligned and their spectral lines overlapped, leading Hsu to believe it was just one star. But as the stars moved in their orbit, the spectral lines shifted in opposite directions, splitting into pairs in later spectral data. Hsu realized there were actually two stars locked into an incredibly tight binary.

Using powerful telescopes at the W.M. Keck Observatory, Hsu decided to observe the phenomenon for himself. On March 13, 2022, the team turned the telescopes toward the constellation Taurus, where the binary system is located, and observed it for two hours. Then, they followed up with more observations in July, October and December. Burgasser said:

When we were making this measurement, we could see things changing over a couple of minutes of observation. Most binaries we follow have orbit periods of years. So, you get a measurement every few months. Then, after a while, you can piece together the puzzle.

With this system, we could see the spectral lines moving apart in real time.

Confirming the model

The observations confirmed what Hsu’s model had predicted. The distance between the two stars is about 1% of the distance between the Earth and the sun. Burgasser said:

This is remarkable, because when they were young, something like 1 million years old, these stars would have been on top of each other.

The team speculates that the stars either migrated toward each other as they evolved, or they could have come together after the ejection of a third — now lost — stellar member. More observations are needed to test these ideas.

Hsu also said that by studying similar star systems researchers can learn more about potentially habitable planets beyond Earth. Ultracool dwarfs are much fainter and dimmer than the sun, so any worlds with liquid water on their surfaces — a crucial ingredient to form and sustain life — would need to be much closer to the star. However, for LP 413-53AB, the habitable zone distance happens to be the same as the stellar orbit, making it impossible to form habitable planets in this system. He said:

These ultracool dwarfs are neighbors of our sun. To identify potentially habitable hosts, it’s helpful to start with our nearby neighbors. But if close binaries are common among ultracool dwarfs, there may be few habitable worlds to be found.

Hsu, Burgasser and their collaborators hope to pinpoint more ultracool dwarf binary systems, to further explore these ideas.

Bottom line: Astronomers have discovered an ultracool dwarf binary system – 2 very low-mass stars orbiting closely – completing an orbit in less than an earthly day.

The post Ultracool dwarf binary stars break records first appeared on EarthSky.

0 Commentaires