Milky Way’s central black hole

Our Milky Way galaxy, like most galaxies we see in the vast universe, has a supermassive black hole at its heart. The black hole has a mass of some 4 million suns. Astronomers call this central black hole Sagittarius A* (pronounced Sagittarius A-star). This week (January 12, 2022), astronomers said the giant black hole at our Milky Way’s heart not only flares irregularly from day to day, but also in the long term. They said the flaring makes Sgr A* unpredictable over long periods of time. Astronomer Alexis Andres from El Salvador initiated the research that ultimately led to the analysis of 15 years of data on Sgr A*. The peer-reviewed journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society will publish the results of the research.

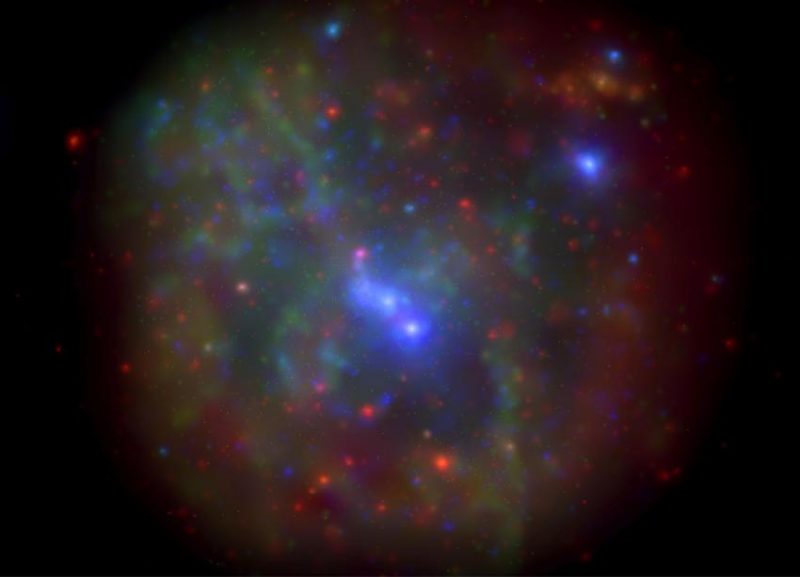

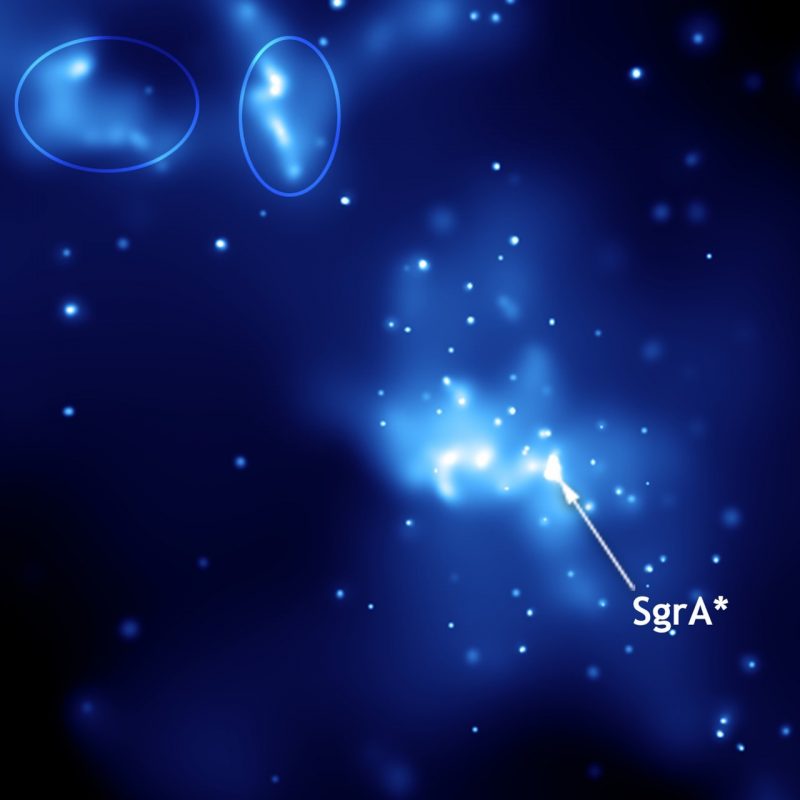

Andres initiated the research in 2019 when he was a summer student at the University of Amsterdam. In the years that followed, he continued his studies of Sgr A*, which is hidden to optical telescopes by intervening gas, dust and stars. Fortunately, Sgr A* is a strong source of radio waves, X-rays and gamma rays. A statement from these astronomers said:

Astronomers have known for decades that Sagittarius A* flashes every day, emitting bursts of radiation that are ten to a hundred times brighter than normal signals observed from the black hole … To find out more about Sagittarius A*’s flares, an international team of astronomers searched for patterns in 15 years of data. That long data set is available because NASA’s Swift satellite has been glancing at the central black hole every three days since 2006.

It turns out that from 2006 to 2008, the area near the black hole was flashing quite a bit. But between 2008 and 2012, it was pretty quiet. And after 2012, the flares increased again.

The researchers could not distinguish a pattern.

Why is it flashing?

Astronomers want to know if the day-to-day (and long-term) flaring of Sgr A* is related to the sorts of extreme activity astronomers see with distant supermassive black holes. These young supermassive black holes – far away in space and time – appear to be devouring vast quantities of material. Our Milky Way’s central black hole wouldn’t be consuming as much material. Because it’s closer to us, we see it nearer to us in time. It’s an older, more evolved and sedate black hole than those in the early universe. But Sgr A* might be devouring something. Or … is something else causing the irregular activity observed from our galaxy’s central black hole? Can astronomers confirm a cause? Not yet. Co-author Jakob van den Eijnden of University of Oxford explained:

… How the flares occur exactly remains unclear. It was previously thought that more flares follow after gaseous clouds or stars pass by the black hole, but there is no evidence for that yet. And we cannot yet confirm the hypothesis that the magnetic properties of the surrounding gas play a role either.

Co-author Nathalie Degenaar at University of Amsterdam supervised both Andres and Van den Eijnden in 2019 as they began studying Sgr A*. She began her studies of this object some time ago, as she was doing her Ph.D., when NASA granted her initial funding. She said:

The long dataset of the Swift observatory did not just happen by accident. And since [my earliest studies], I’ve been applying for prolongation [of funding] regularly. It’s a very special observing program that allows us to conduct a lot of research.

Over the next few years, these astronomers said, they expect to gather enough data to be able to rule out whether the variations in the flares near Sgr A* are due to passing gaseous clouds or stars, or whether something else is going on.

They can’t look away

These astronomers also noted that the environment around Sgr A* has been of interest for years. For example, they noted:

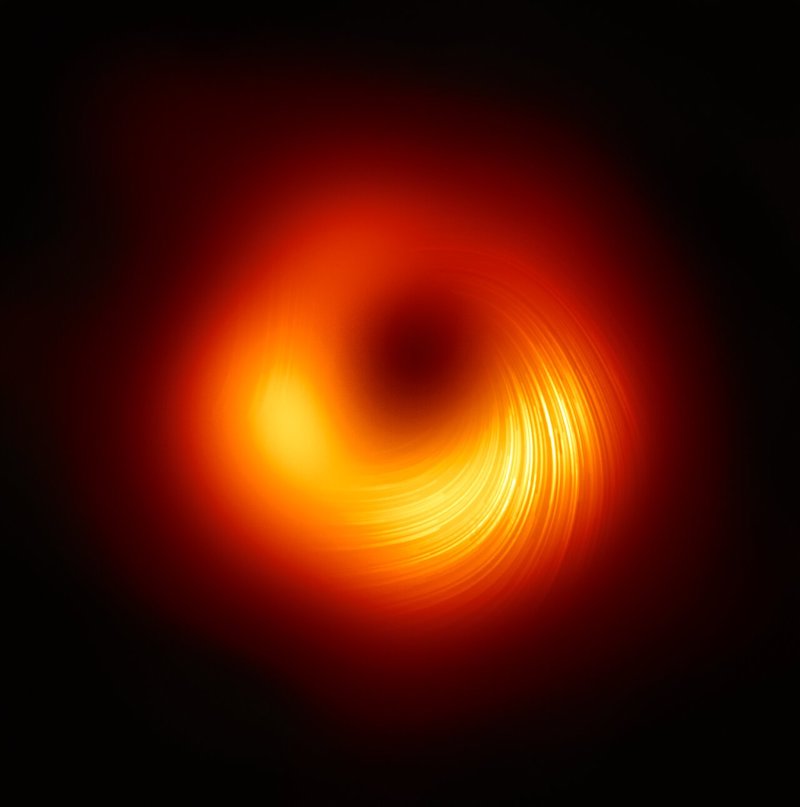

… half of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2020 went to researchers who had spent years tracking the stars that circle the black hole. And an international team of astronomers, with a large share from the Netherlands, is trying to take a picture or a movie of the direct surroundings of the black hole using the Event Horizon Telescope.

Partly because this black hole flares so unpredictably, it is a lot harder to image than, for example, the black hole in galaxy M87, of which the first picture was published in 2019.

Bottom line: Our Milky Way’s central black hole flares unpredictably, both day to day and also over the long term. Astronomers want to know why.

The post Our Milky Way’s central black hole flashes unpredictably first appeared on EarthSky.

0 Commentaires